Ichabod Twilight – American Revolution

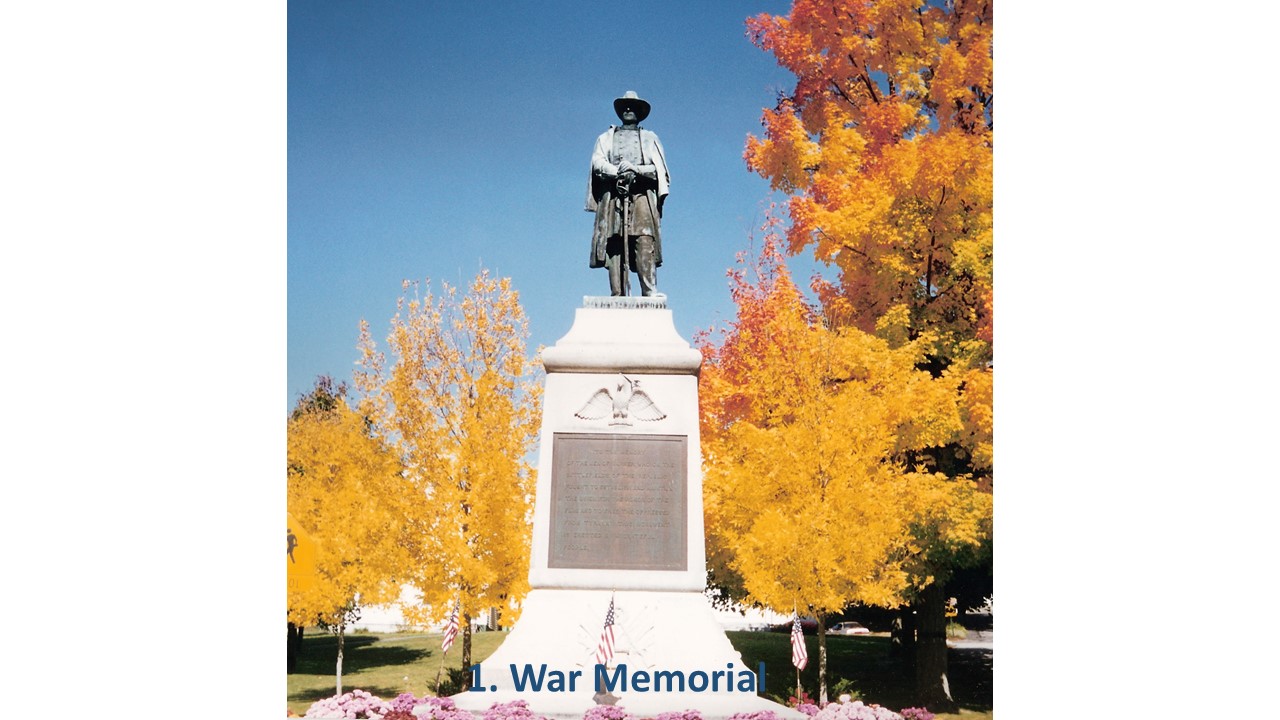

Warner’s 1775 census listed 1 negro or slave for life. Walter Harriman author of the town history said we should not infer that Warner once had an enslaved person because we did not. Ichabod Twilight, a male of color was considered free. Ichabod was in fact a young boy. He was listed on the Roll of Warner men who served in the American Revolution and his name was inscribed on the Soldier’s Monument. But in fact, Twilight did not enroll with Warner men.

Ichabod was born in Boston in late July 1765, which meant he was a ten-year-old boy when the 1775 census was taken. His mother may have been White and his Father Black. Unfortunately, his mother died in childbirth and his father had died before he was born. Twilight may have been bound out or indentured to a family that had moved from the seacoast to the foothills of Mt. Kearsarge.

He left Warner at the age of 14 with intention of enlisting in the army. He moved to Newbury, MA where he signed up for three years with the Massachusetts Regulars although it appears he did not serve at that time. He may have returned to Warner for a short time in the winter of 1781. The following Spring on April 23, 1782, in Exeter he enrolled and was credited to the town of Sandown, NH, receiving l20 for enlisting. He was 17 years old, gave his occupation as farmer, stood 5 foot 3 inches, and was characterized as light in color. Twilight was able to read and write as evidenced by his signature on pension and military records. Twilight served from April 1782 to about June 1783 as a private in the Continental Army, Second NH Regiment, 6th Company stationed in Albany, NY and eventually reassigned south of the Hudson River near Newburgh.

It is not clear where Ichabod lived from 1784-1791. He may have stayed in the Hudson River Valley rather than taking the long walk back to New England. He married a woman by the name of Mary in Plattsburg, NY in 1791. The family would live in Bradford and Corinth, VT and raise six children. Their son Alexander Twilight would be the first person of color to graduate from Middlebury College in 1823. Their youngest son, William moved from Vermont to Massachusetts and then Meredith, NH where he purchased land and married Sarah Crosby. They lived in the towns of Exeter and Hampton, and by 1870 resided in Raymond, NH.

Warner’s 1775 census listed 1 negro or slave for life. Walter Harriman author of the town history said we should not infer that Warner once had an enslaved person because we did not. Ichabod Twilight, a male of color was considered free. Ichabod was in fact a young boy. He was listed on the Roll of Warner men who served in the American Revolution and his name was inscribed on the Soldier’s Monument. But in fact, Twilight did not enroll with Warner men.

Ichabod was born in Boston in late July 1765, which meant he was a ten-year-old boy when the 1775 census was taken. His mother may have been White and his Father Black. Unfortunately, his mother died in childbirth and his father had died before he was born. Twilight may have been bound out or indentured to a family that had moved from the seacoast to the foothills of Mt. Kearsarge.

He left Warner at the age of 14 with intention of enlisting in the army. He moved to Newbury, MA where he signed up for three years with the Massachusetts Regulars although it appears he did not serve at that time. He may have returned to Warner for a short time in the winter of 1781. The following Spring on April 23, 1782, in Exeter he enrolled and was credited to the town of Sandown, NH, receiving l20 for enlisting. He was 17 years old, gave his occupation as farmer, stood 5 foot 3 inches, and was characterized as light in color. Twilight was able to read and write as evidenced by his signature on pension and military records. Twilight served from April 1782 to about June 1783 as a private in the Continental Army, Second NH Regiment, 6th Company stationed in Albany, NY and eventually reassigned south of the Hudson River near Newburgh.

It is not clear where Ichabod lived from 1784-1791. He may have stayed in the Hudson River Valley rather than taking the long walk back to New England. He married a woman by the name of Mary in Plattsburg, NY in 1791. The family would live in Bradford and Corinth, VT and raise six children. Their son Alexander Twilight would be the first person of color to graduate from Middlebury College in 1823. Their youngest son, William moved from Vermont to Massachusetts and then Meredith, NH where he purchased land and married Sarah Crosby. They lived in the towns of Exeter and Hampton, and by 1870 resided in Raymond, NH.

William Bradish – War of 1812

War of 1812 veteran William Bradish was born in Litchfield, NH in 1789. His father Caesar Bradish purchased property in Nottingham West, now Hudson, NH and moved from Litchfield shortly after William’s birth. Caesar was a blacksmith, a skilled laborer, whose profession enabled him to purchase property. In the 1790 census he has a family of six, including daughter Nabby and sons William and Caesar.

In 1795 Caesar Bradish sold his ten acres and moved to Henniker where he died in 1808 at his home on Ray Road. His sons William and Caesar moved over the town line to Warner where they are listed in the 1810 census, each with a family of four. Occupations are not listed that early in the census, so we do not know if Caesar passed on his blacksmithing skills to his sons.

William enlisted as a private under the command of Colonel Daniel Dana on March 3rd, 1814. The 25-year-old William was described as a farmer, 5’8” tall with dark hair, eyes, and skin on his enlistment documents. Bradish fought at Plattsburgh where the American victory included many casualties. It appears Bradish also served in Valentine’s 1st regiment of the Massachusetts military as a waiter. He was discharged in June 1815.

William married afterwards. His wife and daughter living with him in Cavendish, Vermont at the time of the 1820 census. It’s not clear where Bradish lived for the next twenty years but by 1840, he had returned to Warner and was living by himself. Perhaps his wife had died, we don’t know at this point. In 1850 an Elizabeth Jenkins (35) and her two boys, George and Francis, ages six and four are living with William and are listed as mulatto in the census. Elizabeth was likely his daughter.

Bradish worked as a laborer in the neighborhood of Kearsarge Street. The aging Bradish began to receive town aid from 1853-1858 for food, tobacco, alcohol, cordwood, and medical assistance. By 1859, Bradish had moved to the Town Poor Farm where he died of consumption on November 13, 1859, at the age of 70. He is buried in the poor farm cemetery in a grave without a gravestone. The American Legion places a flag for him in the cemetery each year when they honor the town’s veterans.

War of 1812 veteran William Bradish was born in Litchfield, NH in 1789. His father Caesar Bradish purchased property in Nottingham West, now Hudson, NH and moved from Litchfield shortly after William’s birth. Caesar was a blacksmith, a skilled laborer, whose profession enabled him to purchase property. In the 1790 census he has a family of six, including daughter Nabby and sons William and Caesar.

In 1795 Caesar Bradish sold his ten acres and moved to Henniker where he died in 1808 at his home on Ray Road. His sons William and Caesar moved over the town line to Warner where they are listed in the 1810 census, each with a family of four. Occupations are not listed that early in the census, so we do not know if Caesar passed on his blacksmithing skills to his sons.

William enlisted as a private under the command of Colonel Daniel Dana on March 3rd, 1814. The 25-year-old William was described as a farmer, 5’8” tall with dark hair, eyes, and skin on his enlistment documents. Bradish fought at Plattsburgh where the American victory included many casualties. It appears Bradish also served in Valentine’s 1st regiment of the Massachusetts military as a waiter. He was discharged in June 1815.

William married afterwards. His wife and daughter living with him in Cavendish, Vermont at the time of the 1820 census. It’s not clear where Bradish lived for the next twenty years but by 1840, he had returned to Warner and was living by himself. Perhaps his wife had died, we don’t know at this point. In 1850 an Elizabeth Jenkins (35) and her two boys, George and Francis, ages six and four are living with William and are listed as mulatto in the census. Elizabeth was likely his daughter.

Bradish worked as a laborer in the neighborhood of Kearsarge Street. The aging Bradish began to receive town aid from 1853-1858 for food, tobacco, alcohol, cordwood, and medical assistance. By 1859, Bradish had moved to the Town Poor Farm where he died of consumption on November 13, 1859, at the age of 70. He is buried in the poor farm cemetery in a grave without a gravestone. The American Legion places a flag for him in the cemetery each year when they honor the town’s veterans.

John F. Haskell

John Franklin Haskell, son of John Haskell of Warner and Nancy Potter of Andover, was born about 1841. His grandfather was also a John Haskell, perhaps that’s why he was called Franklin or Frank. John Franklin’s military records state that he was born in Chichester, but he grew up in Warner according to census and school records. He was working as a farmer when he enlisted in the Civil War in 1864. He volunteered with other Warner men to fill the town’s quota in the 4th NH regiment. However, Civil War units were segregated by race so John Franklin could not serve with his white neighbors. Instead, he was mustered into the 45th United States Colored Troops. His regiment fought in battles in Virginia pursuing Lee until he surrendered at Appomattox. The regiment was stationed in Texas on the Mexican border where John Franklin served as a teamster until he was mustered out late in 1865.

After the war he was living in Sutton with his parents and siblings working as a laborer, later he was the hired man on a farm in Sutton and lived with that family. He moved to Franklin, then Salisbury in the late 19th century where he was employed as a laborer until his death in 1901. Tragically, he accidently drowned in Tucker Pond in Salisbury. His grave was unmarked until members of the Salisbury Historical Society submitted the research needed to get a government issued veterans grave marker which they installed in late 2019.

John Franklin Haskell, son of John Haskell of Warner and Nancy Potter of Andover, was born about 1841. His grandfather was also a John Haskell, perhaps that’s why he was called Franklin or Frank. John Franklin’s military records state that he was born in Chichester, but he grew up in Warner according to census and school records. He was working as a farmer when he enlisted in the Civil War in 1864. He volunteered with other Warner men to fill the town’s quota in the 4th NH regiment. However, Civil War units were segregated by race so John Franklin could not serve with his white neighbors. Instead, he was mustered into the 45th United States Colored Troops. His regiment fought in battles in Virginia pursuing Lee until he surrendered at Appomattox. The regiment was stationed in Texas on the Mexican border where John Franklin served as a teamster until he was mustered out late in 1865.

After the war he was living in Sutton with his parents and siblings working as a laborer, later he was the hired man on a farm in Sutton and lived with that family. He moved to Franklin, then Salisbury in the late 19th century where he was employed as a laborer until his death in 1901. Tragically, he accidently drowned in Tucker Pond in Salisbury. His grave was unmarked until members of the Salisbury Historical Society submitted the research needed to get a government issued veterans grave marker which they installed in late 2019.

James F. Haskell

John’s cousin James Haskell was born about 1842 in Warner to William Haskell and Caroline Clark. William was a basket maker and Caroline’s father was Anthony Clark, a Revolutionary War veteran, fiddler and dancing master. We’ll learn much more about both William and Anthony later in our tour. James was working as a farmer when he enlisted during the Civil War in 1863. James travelled to Massachusetts to join the newly formed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, made famous by the movie Glory. It was the first regiment formed for Black soldiers in the North.

The 54th saw combat at Fort Wagner, South Carolina in 1863, sustaining heavy casualties, but proving the fighting capabilities of Black soldiers. The Union Army increased enrollment of Black soldiers because of the 54th’s bravery. The regiment fought further battles in Florida and South Carolina until the end of the war. James was wounded at the battle of Honey Hill in South Carolina in November 1864 but returned to active duty and was mustered out in August 1865.

After the war he married Dorcas Paul of Gilmanton, the mother of two children. They lived in Newport where James was employed operating a machine in the woolen mills. Unfortunately, he contracted tuberculosis, a disease commonly spread through textile mills. He was only 28 years old when he died in 1870. He is buried in Salisbury, a town where the Haskell family had roots. His family was able to purchase a Veterans headstone for him.

Dorcas moved to Sanbornton with her children and worked as a housekeeper. She applied for a widow’s pension at the end of her life based on James’ Civil War service.

John’s cousin James Haskell was born about 1842 in Warner to William Haskell and Caroline Clark. William was a basket maker and Caroline’s father was Anthony Clark, a Revolutionary War veteran, fiddler and dancing master. We’ll learn much more about both William and Anthony later in our tour. James was working as a farmer when he enlisted during the Civil War in 1863. James travelled to Massachusetts to join the newly formed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, made famous by the movie Glory. It was the first regiment formed for Black soldiers in the North.

The 54th saw combat at Fort Wagner, South Carolina in 1863, sustaining heavy casualties, but proving the fighting capabilities of Black soldiers. The Union Army increased enrollment of Black soldiers because of the 54th’s bravery. The regiment fought further battles in Florida and South Carolina until the end of the war. James was wounded at the battle of Honey Hill in South Carolina in November 1864 but returned to active duty and was mustered out in August 1865.

After the war he married Dorcas Paul of Gilmanton, the mother of two children. They lived in Newport where James was employed operating a machine in the woolen mills. Unfortunately, he contracted tuberculosis, a disease commonly spread through textile mills. He was only 28 years old when he died in 1870. He is buried in Salisbury, a town where the Haskell family had roots. His family was able to purchase a Veterans headstone for him.

Dorcas moved to Sanbornton with her children and worked as a housekeeper. She applied for a widow’s pension at the end of her life based on James’ Civil War service.

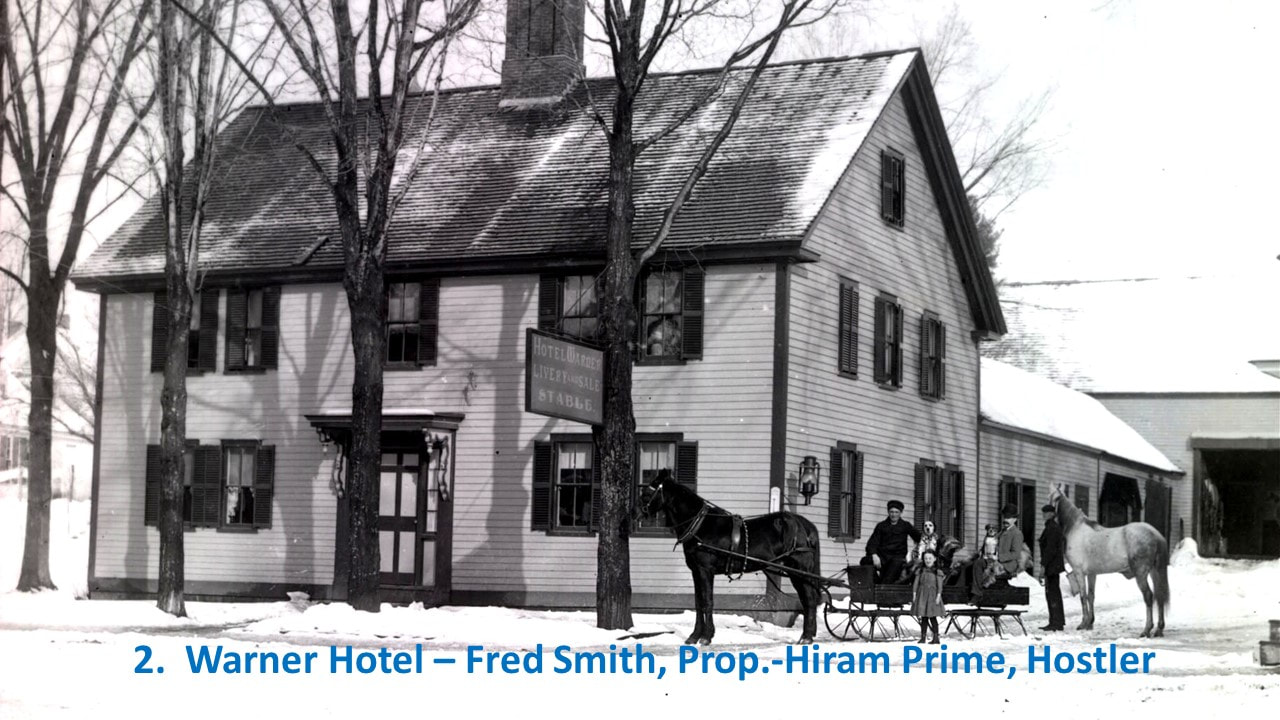

Warner Hotel - Hiram Prime - 5 East Main St (currently the site of Warner Town Hall)

Fred Smith operated the Warner Hotel that stood on the site of the current brick town hall on Main Street. He employed Hiram Prime as the hostler (someone who tended horses) at the time of the 1900 census. Prime was described as a single Black man in the census and both he and his parents as being born in New Hampshire. However, the census taker seems to have paid little attention to recording accurate or thorough information, leaving many columns, including his age and date of birth, blank.

Our current research indicates that Prime may have been lived in Lyons, Wayne County, NY before moving to New Hampshire. He was born in New York state and his parents were born in South Carolina and Alabama. Census takers in Lyons, NY were not consistent in recording his age or the spelling of his last name. The 1870 Federal Census for Lyons, NY lists a Hiram Perrine, age 21, Mulatto, working as a teamster. The 1880 census for the same community lists a Prime family consisting of Hiram, age 25 working as a laborer, his Mother Sarah age 55, and his sister Eliza, 19, working as a servant. A Hiram Pryme was incarcerated for two and a half years in the 1870s for grand larceny. He was described as a laborer from Wayne County. A column noting education has mainly entries of common school or simply poor. Hiram’s education was listed as poor. Further research is needed to prove this is the Hiram Prime who later lived in Warner.

In any case, prior to moving to Warner, Hiram was employed as a hostler and coachman in Concord during the 1890s. He was still an employee of Fred Smith in 1902-03 according to the Concord City & Merrimack Co. Directory. Smith left the hotel business soon after. We have not yet discovered where Hiram was living after 1903.

Fred Smith operated the Warner Hotel that stood on the site of the current brick town hall on Main Street. He employed Hiram Prime as the hostler (someone who tended horses) at the time of the 1900 census. Prime was described as a single Black man in the census and both he and his parents as being born in New Hampshire. However, the census taker seems to have paid little attention to recording accurate or thorough information, leaving many columns, including his age and date of birth, blank.

Our current research indicates that Prime may have been lived in Lyons, Wayne County, NY before moving to New Hampshire. He was born in New York state and his parents were born in South Carolina and Alabama. Census takers in Lyons, NY were not consistent in recording his age or the spelling of his last name. The 1870 Federal Census for Lyons, NY lists a Hiram Perrine, age 21, Mulatto, working as a teamster. The 1880 census for the same community lists a Prime family consisting of Hiram, age 25 working as a laborer, his Mother Sarah age 55, and his sister Eliza, 19, working as a servant. A Hiram Pryme was incarcerated for two and a half years in the 1870s for grand larceny. He was described as a laborer from Wayne County. A column noting education has mainly entries of common school or simply poor. Hiram’s education was listed as poor. Further research is needed to prove this is the Hiram Prime who later lived in Warner.

In any case, prior to moving to Warner, Hiram was employed as a hostler and coachman in Concord during the 1890s. He was still an employee of Fred Smith in 1902-03 according to the Concord City & Merrimack Co. Directory. Smith left the hotel business soon after. We have not yet discovered where Hiram was living after 1903.

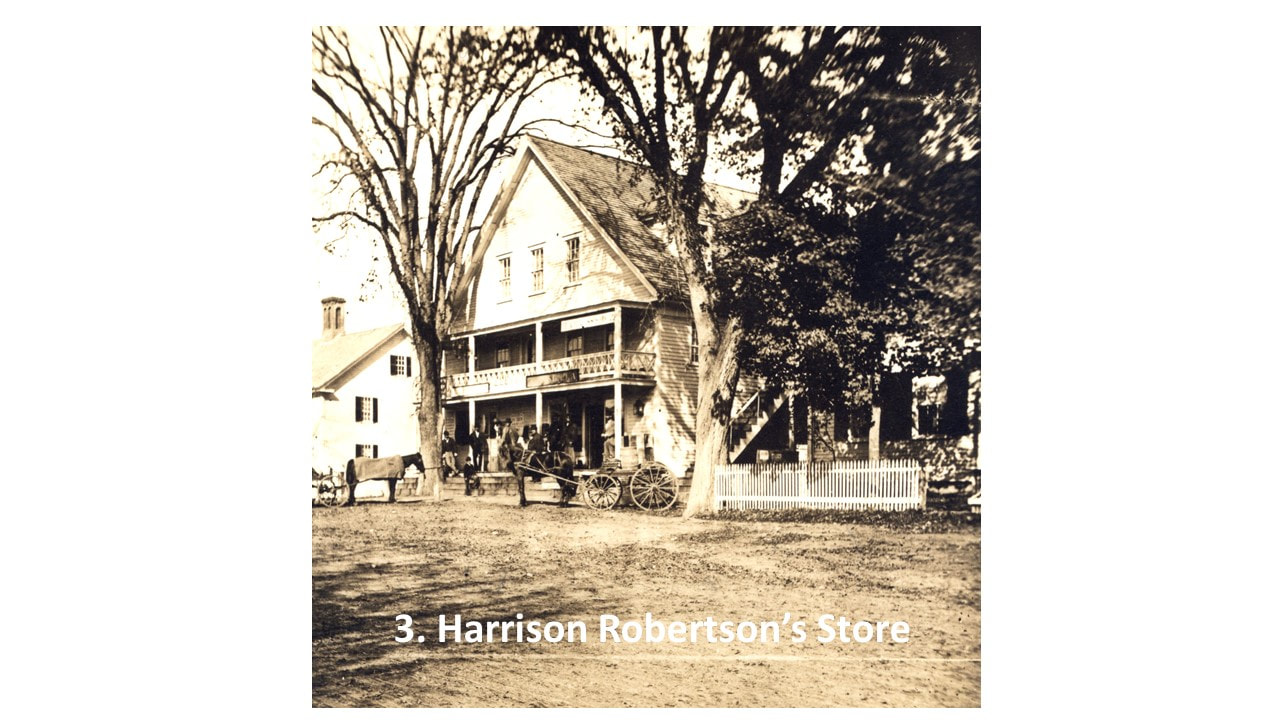

Harrison Robertson’s store - 11 East Main St

Harrison Robertson operated his mercantile store, post office and cooperage business in this building from the mid-1820s to 1844. Robertson would continue to own the property but leased the store to other businessmen over the next several years. He was an original incorporator of the Concord & Claremont Railroad. Harrison bought, sold, and mortgaged properties with Lucy Clark, William and Caroline Haskell, James and Elizabeth Jane Haskell, and Samantha Haskell, the second wife of William. Harrison died in 1862 and his son John took over his business enterprises as well as continuing to do business with Black families.

Cornelius and Harriet Haskell

Harrison Robertson and business partner Christopher McAlpine of Warner leased wood lots around Warner and Hopkinton and hired men to chop wood for them to sell. They employed at least two Black men, David Francis who lived in Warner and later in Hopkinton and Cornelius Haskell of Warner. Cornelius’ birth information was not recorded, so we don’t know yet how he is related to the other Haskell families in town. We do know that he had a half-sister named Harriet. As a teenager Cornelius moved to Pepperell, MA to work as a shoemaker according to the 1850 census. Many rural New Hampshire workers went to rapidly industrializing Massachusetts in search of employment. Cornelius returned and was employed as a wood chopper by 1855.

The reason we know about Cornelius is that he murdered Robertson’s cousin at the shanty on Robertson and McAlpine’s woodlot in the Cloughville section of Hopkinton. Robertson’s cousin, Stephen Washer, in all likelihood sexually harassed Haskell’s significant other Sarah. Sarah and Cornelius beat Washer and Haskell attacked him with an axe. All had been drinking heavily. The murder and their trial were covered by newspapers in the state. Both Cornelius and Sarah were convicted of first-degree murder and were sentenced to be executed. Sarah died shortly after giving birth in prison.

It’s noteworthy that a committee of lawyers from the Merrimack County Bar fought to have Cornelius’ sentence commuted to life in prison. They argued that there was obviously no premeditation and therefore the sentence was unjust. They were successful. Cornelius lived for years in prison. He learned to read and studied religion before his death in 1875.

Cornelius’s sister Harriet was also living at the shanty and witnessed some of the violence. Harriett was only 15 years old at the time. The authorities demanded she give them a $200 surety bond as a guarantee that she would testify. The adult male witnesses were only needed to supply a $100 bond. With no one to help pay that exorbitant sum 15-year-old Harriet was sent to jail to await the trial, her only crime was being in proximity to where a crime happened. None of the adult witnesses sat in jail for a crime they didn’t commit. Newspaper articles reveled in the fact that this wasn’t Harriett’s first time in jail. She was blamed for setting a fire at the Poor Farm in Warner when she was only eleven. She spent five weeks in jail. An eleven year old child spent five weeks in jail.

Contrast her treatment with that of Harrison Robertson’s cousin Stephen Washer. Sarah Haskell was not the first woman he probably harassed and there was history of him committing violent acts. But because he was white and from a good family he was sheltered by his wealthy family and spoken highly of in the newspaper articles recounting his murder.

We don’t yet know how Harriet fared in the rest of her life.

Harrison Robertson operated his mercantile store, post office and cooperage business in this building from the mid-1820s to 1844. Robertson would continue to own the property but leased the store to other businessmen over the next several years. He was an original incorporator of the Concord & Claremont Railroad. Harrison bought, sold, and mortgaged properties with Lucy Clark, William and Caroline Haskell, James and Elizabeth Jane Haskell, and Samantha Haskell, the second wife of William. Harrison died in 1862 and his son John took over his business enterprises as well as continuing to do business with Black families.

Cornelius and Harriet Haskell

Harrison Robertson and business partner Christopher McAlpine of Warner leased wood lots around Warner and Hopkinton and hired men to chop wood for them to sell. They employed at least two Black men, David Francis who lived in Warner and later in Hopkinton and Cornelius Haskell of Warner. Cornelius’ birth information was not recorded, so we don’t know yet how he is related to the other Haskell families in town. We do know that he had a half-sister named Harriet. As a teenager Cornelius moved to Pepperell, MA to work as a shoemaker according to the 1850 census. Many rural New Hampshire workers went to rapidly industrializing Massachusetts in search of employment. Cornelius returned and was employed as a wood chopper by 1855.

The reason we know about Cornelius is that he murdered Robertson’s cousin at the shanty on Robertson and McAlpine’s woodlot in the Cloughville section of Hopkinton. Robertson’s cousin, Stephen Washer, in all likelihood sexually harassed Haskell’s significant other Sarah. Sarah and Cornelius beat Washer and Haskell attacked him with an axe. All had been drinking heavily. The murder and their trial were covered by newspapers in the state. Both Cornelius and Sarah were convicted of first-degree murder and were sentenced to be executed. Sarah died shortly after giving birth in prison.

It’s noteworthy that a committee of lawyers from the Merrimack County Bar fought to have Cornelius’ sentence commuted to life in prison. They argued that there was obviously no premeditation and therefore the sentence was unjust. They were successful. Cornelius lived for years in prison. He learned to read and studied religion before his death in 1875.

Cornelius’s sister Harriet was also living at the shanty and witnessed some of the violence. Harriett was only 15 years old at the time. The authorities demanded she give them a $200 surety bond as a guarantee that she would testify. The adult male witnesses were only needed to supply a $100 bond. With no one to help pay that exorbitant sum 15-year-old Harriet was sent to jail to await the trial, her only crime was being in proximity to where a crime happened. None of the adult witnesses sat in jail for a crime they didn’t commit. Newspaper articles reveled in the fact that this wasn’t Harriett’s first time in jail. She was blamed for setting a fire at the Poor Farm in Warner when she was only eleven. She spent five weeks in jail. An eleven year old child spent five weeks in jail.

Contrast her treatment with that of Harrison Robertson’s cousin Stephen Washer. Sarah Haskell was not the first woman he probably harassed and there was history of him committing violent acts. But because he was white and from a good family he was sheltered by his wealthy family and spoken highly of in the newspaper articles recounting his murder.

We don’t yet know how Harriet fared in the rest of her life.

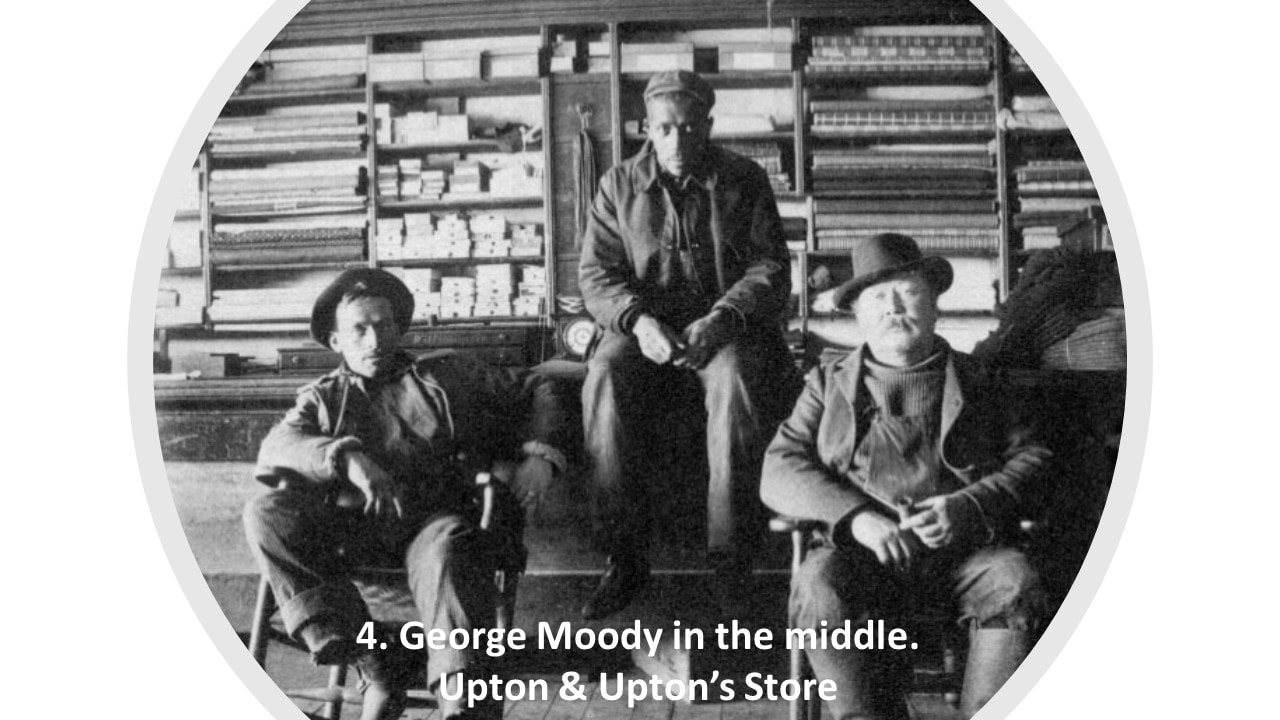

Upton & Upton – photo of George Moody

George and Edward Upton (leased or purchased) the Robertson store in 1880 and operated it for the next thirty years. George Upton was interested in photography and built a camera to take cyanotype photographs which is the process of creating a photographic blueprint. He shot images of his family, friends and scenes around Warner. Upton took this photo of George Moody sitting on a store counter, visiting with his friends, Fred Drown and Frank Page.

George Moody

George Moody was born in 1874 in Pittsfield the son of Charles & Mary Haskell Moody. The Moody family was still in Pittsfield for the 1880 census. George met Cora Belle, the daughter of Nathaniel and Mary Jane Robinson. They have three children between 1896 and 1898: Mary, Louisa and Walter. Walter died on pneumonia at the age of 1. George and Cora wed on August 2, 1899, for a short period of time. By the time of the 1900 Warner census on June 19th they have separated. Cora with daughter Mary was living with the Morrison family above Cunningham Pond as a servant.

George married Cora Heath on July 11, 1903, in Suncook. But the marriage didn’t last as George was living with his mother and extended family on Poverty Plains Road in Warner by the 1910 census and working as a farm laborer. Three years later he married Emma Hunt in Westmoreland. He died of heart disease on December 1, 1915, at the home of brother, Harry Otto Moody near Broad Cove on the Contoocook River. George was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Penacook.

George and Edward Upton (leased or purchased) the Robertson store in 1880 and operated it for the next thirty years. George Upton was interested in photography and built a camera to take cyanotype photographs which is the process of creating a photographic blueprint. He shot images of his family, friends and scenes around Warner. Upton took this photo of George Moody sitting on a store counter, visiting with his friends, Fred Drown and Frank Page.

George Moody

George Moody was born in 1874 in Pittsfield the son of Charles & Mary Haskell Moody. The Moody family was still in Pittsfield for the 1880 census. George met Cora Belle, the daughter of Nathaniel and Mary Jane Robinson. They have three children between 1896 and 1898: Mary, Louisa and Walter. Walter died on pneumonia at the age of 1. George and Cora wed on August 2, 1899, for a short period of time. By the time of the 1900 Warner census on June 19th they have separated. Cora with daughter Mary was living with the Morrison family above Cunningham Pond as a servant.

George married Cora Heath on July 11, 1903, in Suncook. But the marriage didn’t last as George was living with his mother and extended family on Poverty Plains Road in Warner by the 1910 census and working as a farm laborer. Three years later he married Emma Hunt in Westmoreland. He died of heart disease on December 1, 1915, at the home of brother, Harry Otto Moody near Broad Cove on the Contoocook River. George was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Penacook.

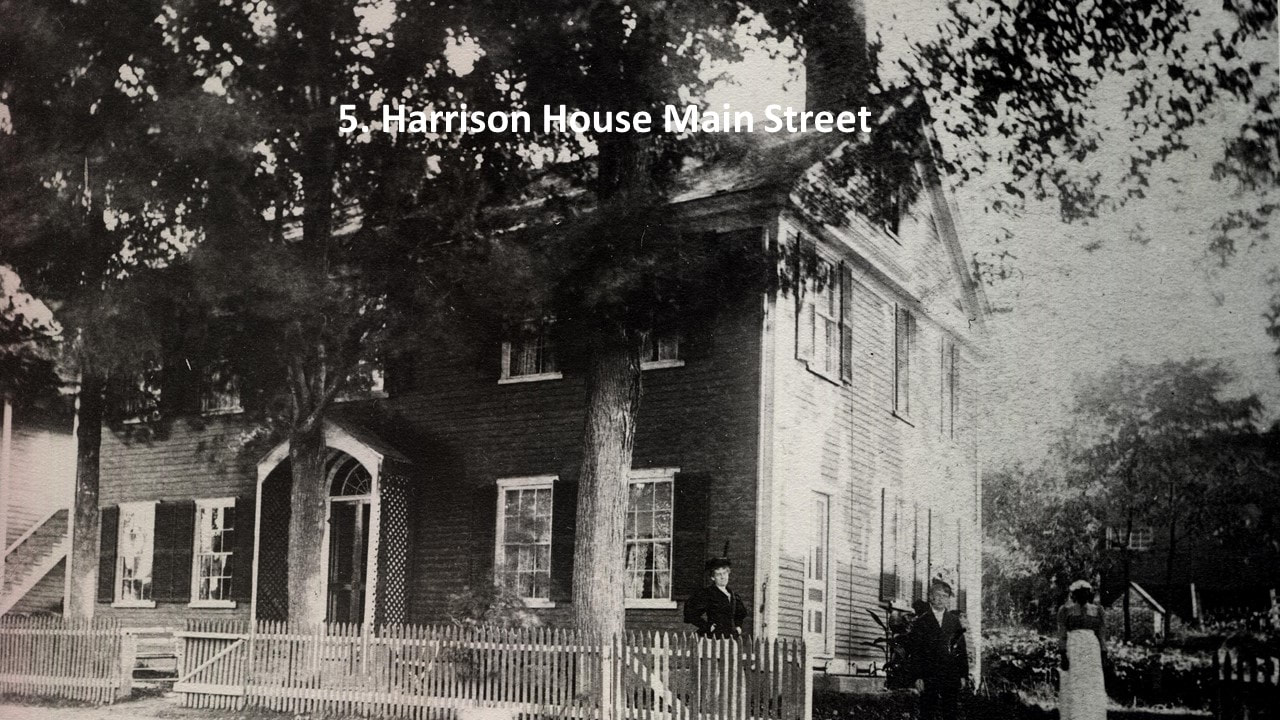

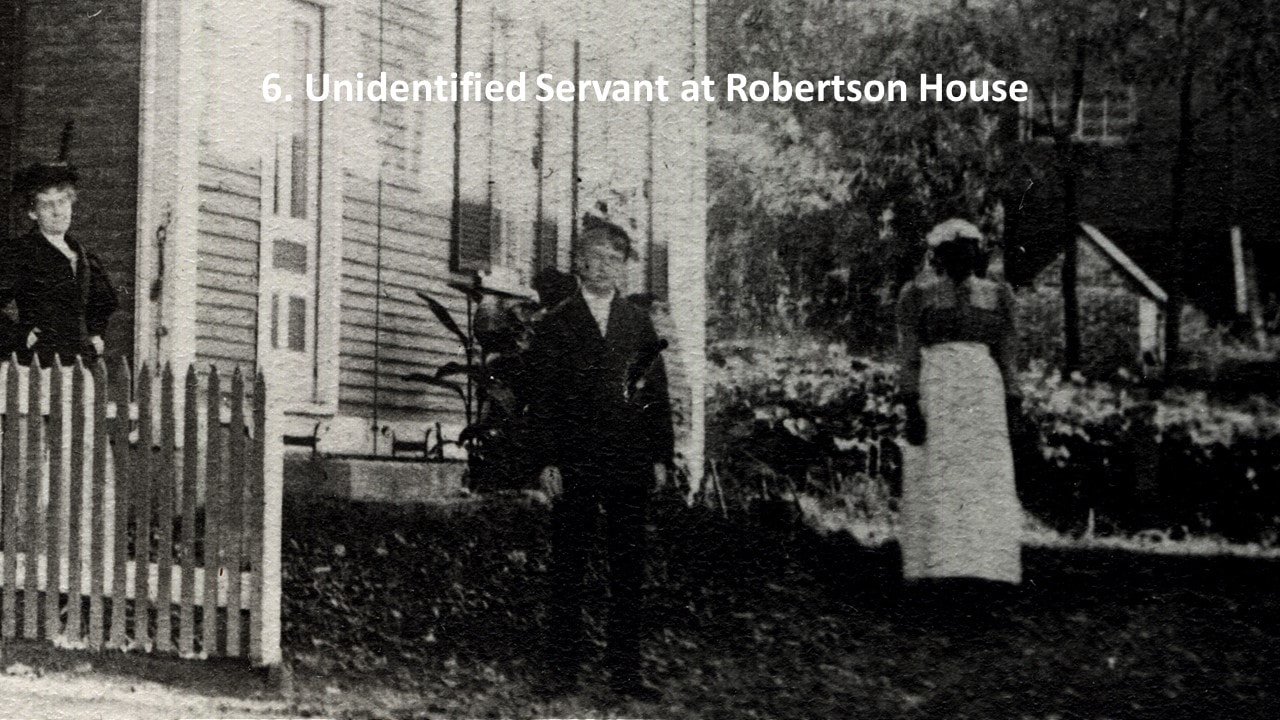

Robertson House - unidentified woman - 15 East Main St

After the Civil War Black men and women from the south came north in search of work. Usually, the only jobs open to them were as laborers and domestic servants, despite any specialized skills they may have had in the south. Several wealthy families in Warner employed Black domestic servants in their household, including the Robertson’s.

An unidentified domestic servant stands toward the background of this photo of the Robertson mansion. Her status as a servant is marked by her dress.

Prior to the Civil War families employed their neighbor’s daughters to help with housework. They were not considered servants. They were not made to wear distinctive clothing that marked them as lower status than their employers. After the Civil War wealthy households wished to display their status by employing domestic servants. Not wishing to be treated as servants, local white women could opt to work in mills instead. Black women did not have the luxury of that choice. Domestic service was one of the few options available to them. Wealthy families looking for domestic servants could hire Irish immigrant women or Black women. Employers assumed that southern Black women would work for less money and be more subservient than Irish immigrants. The underlying racist assumption being that life in the south had conditioned Black women to know their place.

After the Civil War Black men and women from the south came north in search of work. Usually, the only jobs open to them were as laborers and domestic servants, despite any specialized skills they may have had in the south. Several wealthy families in Warner employed Black domestic servants in their household, including the Robertson’s.

An unidentified domestic servant stands toward the background of this photo of the Robertson mansion. Her status as a servant is marked by her dress.

Prior to the Civil War families employed their neighbor’s daughters to help with housework. They were not considered servants. They were not made to wear distinctive clothing that marked them as lower status than their employers. After the Civil War wealthy households wished to display their status by employing domestic servants. Not wishing to be treated as servants, local white women could opt to work in mills instead. Black women did not have the luxury of that choice. Domestic service was one of the few options available to them. Wealthy families looking for domestic servants could hire Irish immigrant women or Black women. Employers assumed that southern Black women would work for less money and be more subservient than Irish immigrants. The underlying racist assumption being that life in the south had conditioned Black women to know their place.

Education – School Street School (no longer standing)

Eve Allegra Raimon wrote in Miss March’s Uncommon School Reform: “New Hampshire was an early advocate for a broader New England effort to assimilate European immigrants by introducing greater systematization and regulation into public schooling. In 1827 it passed an act establishing school districts and requiring them to be supported by yearly tax assessments. It also raised the qualifications for teachers and required students to be “well supplied with books at the expense of the parents, masters, or guardians and in case they are not able, at the public expense.” Warner town reports often refer to supplying schoolbooks for the poor.

“In Common Schools, Their Present Conditions and Future Prospects, by a Teacher (1844), New Hampshire educators John F. Brown and Asa McFarland assert that, “Without good teaching, a school is but a name. We want better teachers, and more teachers for all classes of society; for rich and poor; for children and adults.” Whether or not New Hampshire’s common schools routinely welcomed students from diverse class backgrounds in actuality, educators’ public pronouncements make effusive promises regarding social inclusiveness.”

This looks good on paper but in reality, one needs to keep in mind that in 1834 a group of New Hampshire abolitionists decided to establish an integrated school for Black students in Canaan called Noyes Academy. There were 14 black students and 28 white students enrolled at Noyes. An incredibly angry mob of White anti-abolitionists, mostly men gathered in front of the school with torches, axes, and club with a plan to destroy it. The men were threatened with legal actions and disbanded to reorganize, hold a town meeting, a vote was taken to protect their actions. They returned to the school on August 10th, with teams of oxen and chains and tore the school off its foundation. The Black students had to flee under the cover of darkness.

Living in the neighboring town of Webster in 1850 were True Peters, a Black basket maker and Sophia Cogswell. Peter’s son Joseph (15) and daughter Melissa (13) and Augusta Clark (16) were denied attendance at Corser Hill school on the vote of that school district. They were allowed to attend North Water Street school a further distance from their home. By the 1860 census the families had left Webster.

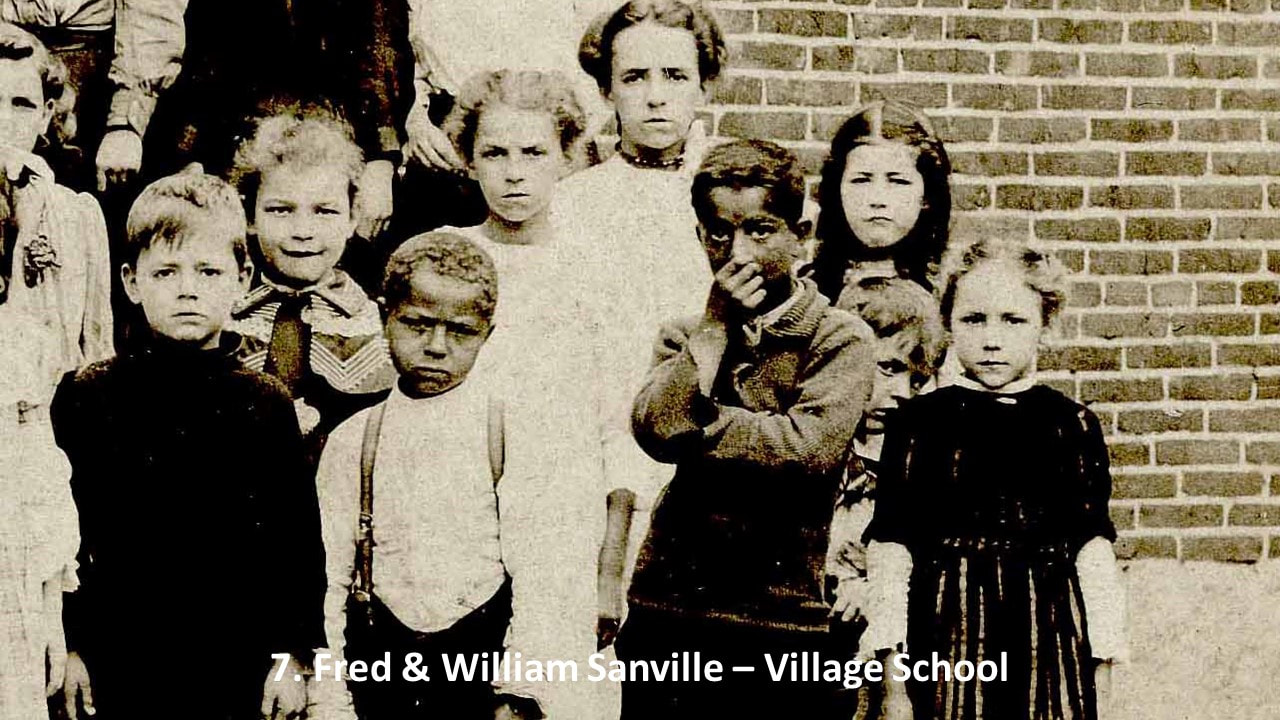

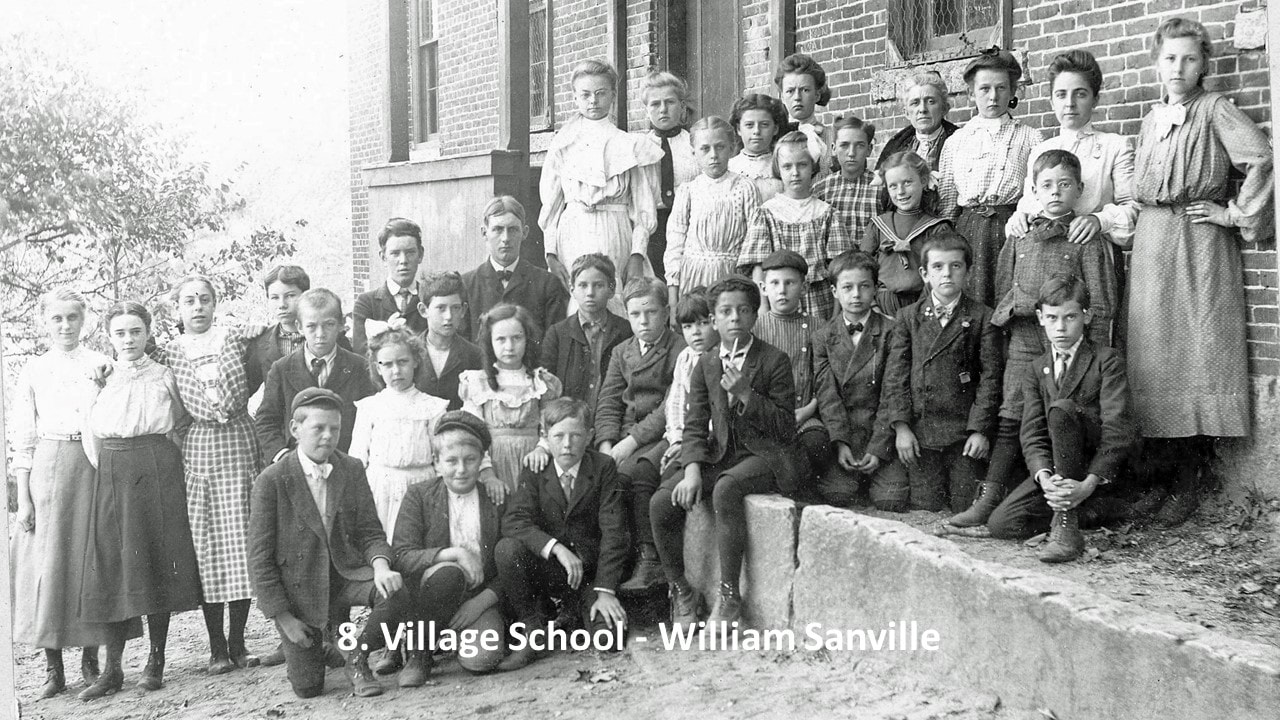

The Warner Historical Society does not have a complete set of school records but the ones we do record the names of children, age, terms, attendance, tardiness, and grades. Children of color attended various one-room schoolhouses in Warner including Burnt Hill, Roby, Waterloo, and this Village school (1854-1862) on School Street.

The John Haskell family lived on Couchtown Road and John worked as a laborer. Depending on where he was working, near their residence or in the Village, may have determined if his children; Caroline, John Franklin, Sarah, and William, attended Burnt Hill or the Village school on any given year. Their cousin Harriet, half-sister of Cornelius attended school with them in 1854.

James the only child of William Haskell, the basket maker and Caroline Haskell, the daughter of Anthony Clark had a short walk from Main Street and attended school until the age of 19. He enrolled in the Civil War soon after.

Joseph and Lucinda were the children of George Washington and Eliza Jane Clark. George, son of Anthony and Lucy Clark had fallen ill in the early 1850s and became the recipient of town aid to paupers not on the Poor Farm. He died in 1856 leaving his widow Eliza and the two children. They were living on the road to Sutton and had a walk of two miles.

From 1901 – 1904 cousins and siblings William, Henry, Minnie, Bertie, Freddie and Sadie Sanville, Georgianna and Marchia Austin, Lillian Haines, Eva, and Mary Jane Chase attended this school. They were living on the Plains Road closer to Davisville than the village but again perhaps one of the men in the family was working in the village and brought them to school.

Eve Allegra Raimon wrote in Miss March’s Uncommon School Reform: “New Hampshire was an early advocate for a broader New England effort to assimilate European immigrants by introducing greater systematization and regulation into public schooling. In 1827 it passed an act establishing school districts and requiring them to be supported by yearly tax assessments. It also raised the qualifications for teachers and required students to be “well supplied with books at the expense of the parents, masters, or guardians and in case they are not able, at the public expense.” Warner town reports often refer to supplying schoolbooks for the poor.

“In Common Schools, Their Present Conditions and Future Prospects, by a Teacher (1844), New Hampshire educators John F. Brown and Asa McFarland assert that, “Without good teaching, a school is but a name. We want better teachers, and more teachers for all classes of society; for rich and poor; for children and adults.” Whether or not New Hampshire’s common schools routinely welcomed students from diverse class backgrounds in actuality, educators’ public pronouncements make effusive promises regarding social inclusiveness.”

This looks good on paper but in reality, one needs to keep in mind that in 1834 a group of New Hampshire abolitionists decided to establish an integrated school for Black students in Canaan called Noyes Academy. There were 14 black students and 28 white students enrolled at Noyes. An incredibly angry mob of White anti-abolitionists, mostly men gathered in front of the school with torches, axes, and club with a plan to destroy it. The men were threatened with legal actions and disbanded to reorganize, hold a town meeting, a vote was taken to protect their actions. They returned to the school on August 10th, with teams of oxen and chains and tore the school off its foundation. The Black students had to flee under the cover of darkness.

Living in the neighboring town of Webster in 1850 were True Peters, a Black basket maker and Sophia Cogswell. Peter’s son Joseph (15) and daughter Melissa (13) and Augusta Clark (16) were denied attendance at Corser Hill school on the vote of that school district. They were allowed to attend North Water Street school a further distance from their home. By the 1860 census the families had left Webster.

The Warner Historical Society does not have a complete set of school records but the ones we do record the names of children, age, terms, attendance, tardiness, and grades. Children of color attended various one-room schoolhouses in Warner including Burnt Hill, Roby, Waterloo, and this Village school (1854-1862) on School Street.

The John Haskell family lived on Couchtown Road and John worked as a laborer. Depending on where he was working, near their residence or in the Village, may have determined if his children; Caroline, John Franklin, Sarah, and William, attended Burnt Hill or the Village school on any given year. Their cousin Harriet, half-sister of Cornelius attended school with them in 1854.

James the only child of William Haskell, the basket maker and Caroline Haskell, the daughter of Anthony Clark had a short walk from Main Street and attended school until the age of 19. He enrolled in the Civil War soon after.

Joseph and Lucinda were the children of George Washington and Eliza Jane Clark. George, son of Anthony and Lucy Clark had fallen ill in the early 1850s and became the recipient of town aid to paupers not on the Poor Farm. He died in 1856 leaving his widow Eliza and the two children. They were living on the road to Sutton and had a walk of two miles.

From 1901 – 1904 cousins and siblings William, Henry, Minnie, Bertie, Freddie and Sadie Sanville, Georgianna and Marchia Austin, Lillian Haines, Eva, and Mary Jane Chase attended this school. They were living on the Plains Road closer to Davisville than the village but again perhaps one of the men in the family was working in the village and brought them to school.

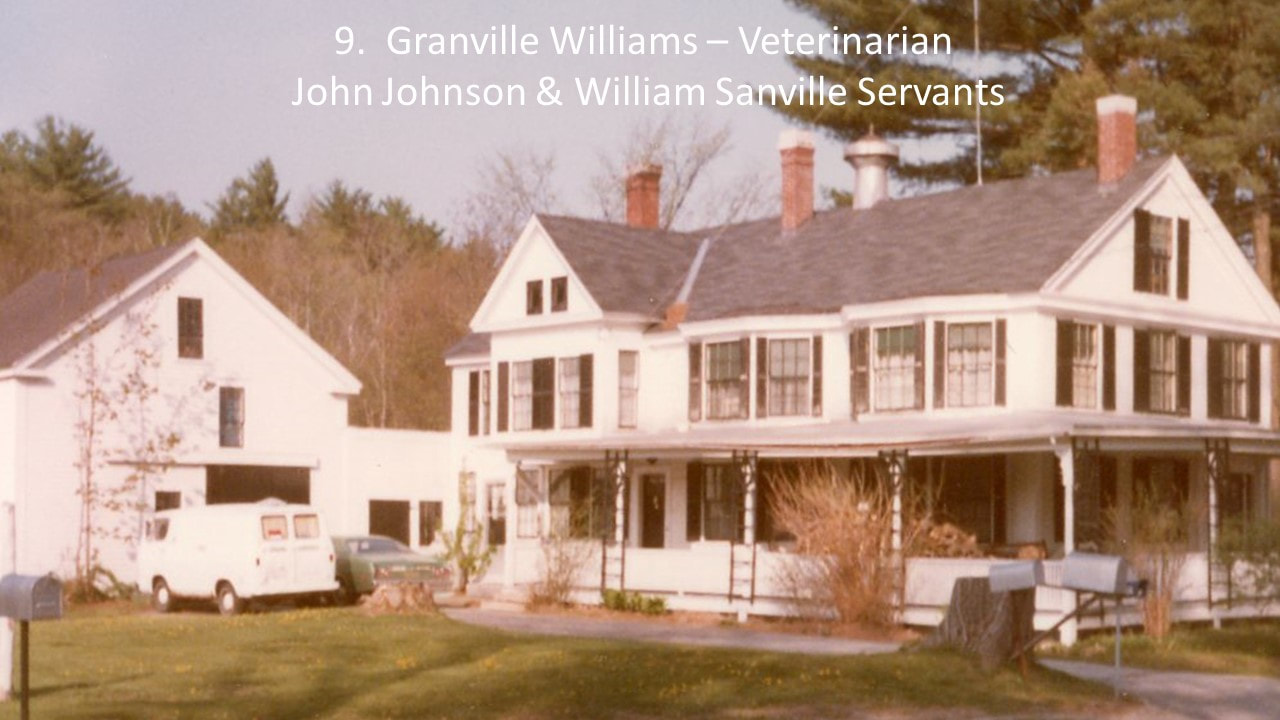

John H Johnson & William Sanville at Grenville Williams House - 70 East Main St

The 1910 Warner census indicates that Grenville Williams, a veterinarian, was renting this home on Main Street with his wife Effie, who operated a boarding house. Living with them was their married daughter Hazel Rogers and Black servants John H. Johnson and William Sanville. John was thirty-four, born in Massachusetts and single. William Sanville was eighteen and was no longer attending the village school in Warner.

Johnson and Sanville were assisting Williams with his veterinarian practice, taking care of animals, and doing farm chores for the boarding house.

In the January 27th issue of the local paper, John Johnson was arrested for drunkenness and disturbing the peace and was placed in the “cage” at the Warner town hall. At sentencing he was fined $5 and costs which amounted to $14. Unable to pay these fees he was taken to the Merrimack County jail in North Boscawen for a stay of 75 days. Johnson’s inability to pay is reminiscent of today’s criminal justice system where a disproportionate number of people of color are incarcerated while waiting to be charged or awaiting trial because they are unable to pay bail. We do not know where Johnson goes after being released from jail.

William Sanville was born in Warner in 1892, to Wilfred (Fred) and Annie Moody Sanville. He grew up on Poverty Plains Road with four younger siblings: Minnie, Fred, Sadie, and Albert or Bertie. Their mother Annie died in 1903 from consumption. It seems that after Annie’s death William may have started working for Grenville as he continued attending the Village school. In reviewing school photographs, he seems better fed and clothed during this period of his life. Although William lived and worked with Grenville, he remained close with his family. He is noted as living with them in Concord and Amherst, NH and Lowell, MA.

When World War 1 broke out the Sanville’s were in Lowell, MA. William and his brother Fred enlisted from there and served overseas in the Yankee Division. This is interesting because the army was not integrated during World War I and the Yankee Division was a white division. Was the family passing for white? Passing is a complicated and nuanced topic that we are just beginning to grapple with. We see in the census that individuals can appear as Black, mulatto or white in different times and places. That points to the subjective nature of race. In the case of the census race is in the eyes of the census taker. What we need to learn much more about is how individuals thought of themselves and how they navigated in a world where race affected and still affects individuals’ safety, health, and economic security.

William was severely wounded and discharged February 13, 1919. He married Rose Boyle a week later in Boscawen, NH. They had a daughter, Helen within a year. William was working in a logging camp as a teamster in Rindge, NH according to the 1920 census and in Andover, NH as a teamster in the 1930 census. Helen may have died as a baby as she isn’t listed in the census records.

In 1937 William begins serving nine years in state prison for statutory rape and was discharged in 1944. Rose and William may have divorced while he was in prison, as he married Florence Austin on March 20, 1946. They continued to live in the area and had several children: Thomas, Dennis, Wilfred, and Robert. William died in Laconia in January 1966 and was buried at Blossom Hill Cemetery in Concord with a military marker.

The 1910 Warner census indicates that Grenville Williams, a veterinarian, was renting this home on Main Street with his wife Effie, who operated a boarding house. Living with them was their married daughter Hazel Rogers and Black servants John H. Johnson and William Sanville. John was thirty-four, born in Massachusetts and single. William Sanville was eighteen and was no longer attending the village school in Warner.

Johnson and Sanville were assisting Williams with his veterinarian practice, taking care of animals, and doing farm chores for the boarding house.

In the January 27th issue of the local paper, John Johnson was arrested for drunkenness and disturbing the peace and was placed in the “cage” at the Warner town hall. At sentencing he was fined $5 and costs which amounted to $14. Unable to pay these fees he was taken to the Merrimack County jail in North Boscawen for a stay of 75 days. Johnson’s inability to pay is reminiscent of today’s criminal justice system where a disproportionate number of people of color are incarcerated while waiting to be charged or awaiting trial because they are unable to pay bail. We do not know where Johnson goes after being released from jail.

William Sanville was born in Warner in 1892, to Wilfred (Fred) and Annie Moody Sanville. He grew up on Poverty Plains Road with four younger siblings: Minnie, Fred, Sadie, and Albert or Bertie. Their mother Annie died in 1903 from consumption. It seems that after Annie’s death William may have started working for Grenville as he continued attending the Village school. In reviewing school photographs, he seems better fed and clothed during this period of his life. Although William lived and worked with Grenville, he remained close with his family. He is noted as living with them in Concord and Amherst, NH and Lowell, MA.

When World War 1 broke out the Sanville’s were in Lowell, MA. William and his brother Fred enlisted from there and served overseas in the Yankee Division. This is interesting because the army was not integrated during World War I and the Yankee Division was a white division. Was the family passing for white? Passing is a complicated and nuanced topic that we are just beginning to grapple with. We see in the census that individuals can appear as Black, mulatto or white in different times and places. That points to the subjective nature of race. In the case of the census race is in the eyes of the census taker. What we need to learn much more about is how individuals thought of themselves and how they navigated in a world where race affected and still affects individuals’ safety, health, and economic security.

William was severely wounded and discharged February 13, 1919. He married Rose Boyle a week later in Boscawen, NH. They had a daughter, Helen within a year. William was working in a logging camp as a teamster in Rindge, NH according to the 1920 census and in Andover, NH as a teamster in the 1930 census. Helen may have died as a baby as she isn’t listed in the census records.

In 1937 William begins serving nine years in state prison for statutory rape and was discharged in 1944. Rose and William may have divorced while he was in prison, as he married Florence Austin on March 20, 1946. They continued to live in the area and had several children: Thomas, Dennis, Wilfred, and Robert. William died in Laconia in January 1966 and was buried at Blossom Hill Cemetery in Concord with a military marker.

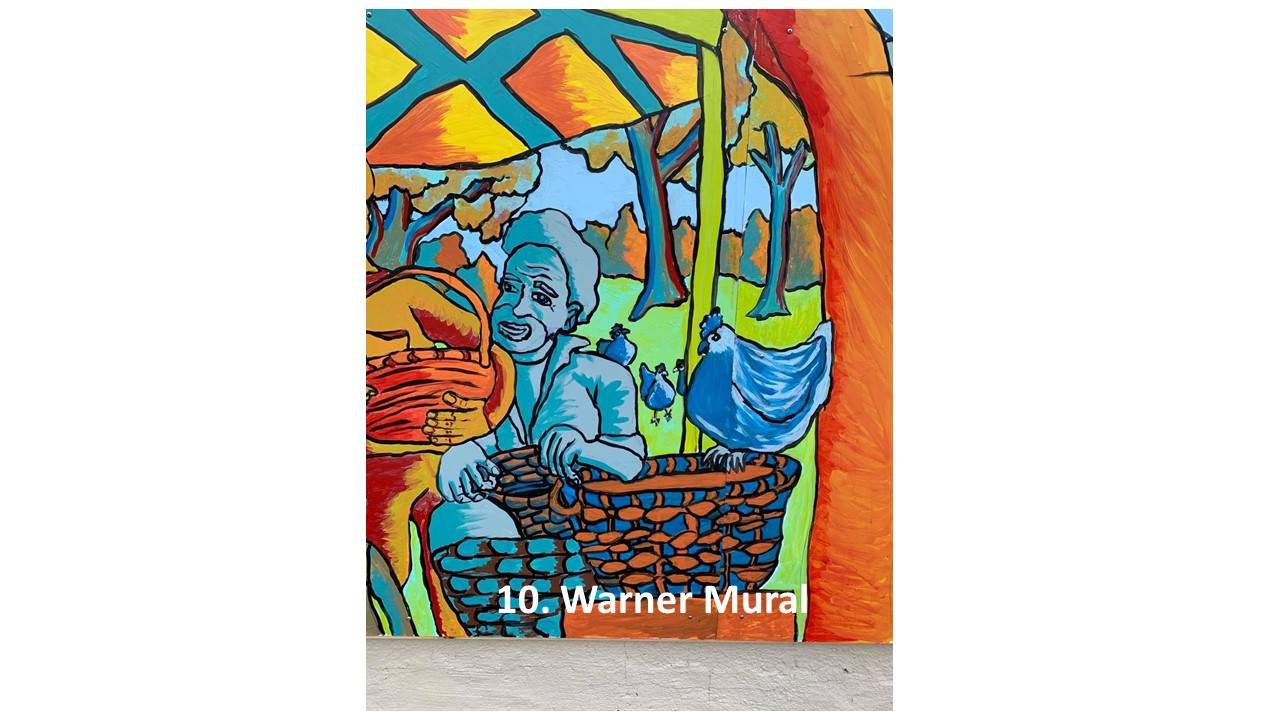

Mural - 2 East Main St

The Economic Development Committee of commissioned this mural showing modern and historic scenes of Warner. The Warner Historical Society provided suggestions, including that Abenaki and Black history be represented. We are very pleased that the committee and artist Jyl Dittbenner included Abenaki representations based on suggestions from Abenaki residents and that Warner’s Black basket maker William Haskell was included. Our last stop on the walking tour today is at Haskell’s house.

The Economic Development Committee of commissioned this mural showing modern and historic scenes of Warner. The Warner Historical Society provided suggestions, including that Abenaki and Black history be represented. We are very pleased that the committee and artist Jyl Dittbenner included Abenaki representations based on suggestions from Abenaki residents and that Warner’s Black basket maker William Haskell was included. Our last stop on the walking tour today is at Haskell’s house.

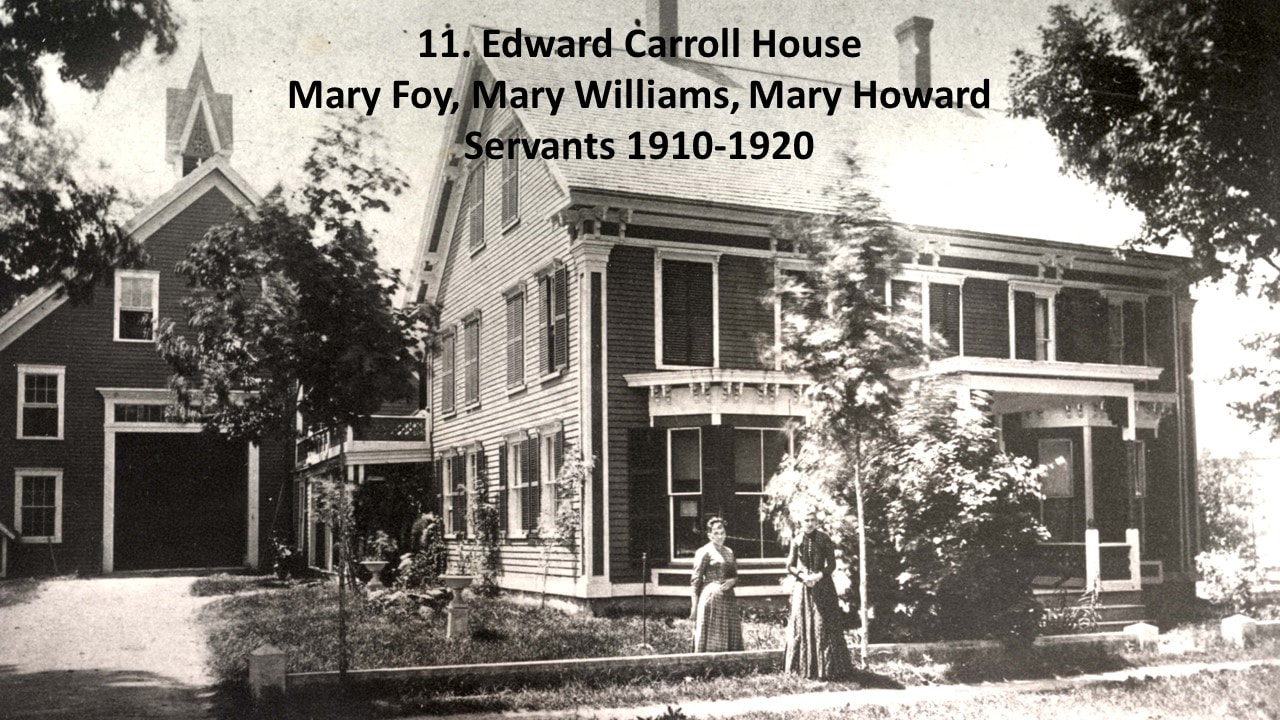

Carroll’s House - 9 West Main St

Author Isabel Wilkerson in her book The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, characterizes Black migration north after the Civil War as first a trickle, then a stream as Jim Crow laws took hold in the 1890s and finally “a river, uncontrolled and uncontrollable” during and following World War I.

Three women made the journey north to labor in this house as the great migration was changing from a stream to an uncontrolled river. The 1900, 1910 & 1920 census show a domestic servant employed by the Carroll family who owned this house at the time. There is a different woman in each census, Mary Corbett, Mary Foy, and Mary Howard. Each was born in North Carolina. Two of the women were married at the time of their employment, Mary Corbett had three children. Their husbands and children were not in Warner. Mary Foy was unmarried at the time. If I have identified her correctly in subsequent census’, she returned to North Carolina and worked with her husband on their farm.

Imagine the difficult choices these women had to make to leave their families and travel North. Who knows how often they were able to return home to see husband, children and other family members? Imagine coming to a small rural town, not having a Black community to socialize with, to turn to in times of need, to commiserate with, to worship with.

In 1900 the Carroll household consisted of businessman Edward H. Carroll, his wife Susie, a music teacher, their nineteen-year-old son Edward Lee, his wife Edith and Mary Corbett. Corbett was thirty-four and was hired prior t0 1900 to take care of the household when Edward was a child.

By 1910 Edward Lee, known as Lee, to differentiate himself from his father, had joined the family business. Edith had given birth two years earlier to a son, Edward H., and Mary Foy had joined the household as domestic servant. Mary Corbett was living with and working for a family in Hopkinton, NH.

Tragedy would strike the Carroll family in the next decade. Edward, the father died of heart disease in 1917. His son Lee died during the flu epidemic in January 1919. In 1920 the census shows that Susie and Edith were managing the household with the help of domestic servant Mary Howard and trying to keep their husbands’ businesses operating. Young Edward and James were 12 and 6 years old. Mary Howard age 38 had her hands full.

Author Isabel Wilkerson in her book The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, characterizes Black migration north after the Civil War as first a trickle, then a stream as Jim Crow laws took hold in the 1890s and finally “a river, uncontrolled and uncontrollable” during and following World War I.

Three women made the journey north to labor in this house as the great migration was changing from a stream to an uncontrolled river. The 1900, 1910 & 1920 census show a domestic servant employed by the Carroll family who owned this house at the time. There is a different woman in each census, Mary Corbett, Mary Foy, and Mary Howard. Each was born in North Carolina. Two of the women were married at the time of their employment, Mary Corbett had three children. Their husbands and children were not in Warner. Mary Foy was unmarried at the time. If I have identified her correctly in subsequent census’, she returned to North Carolina and worked with her husband on their farm.

Imagine the difficult choices these women had to make to leave their families and travel North. Who knows how often they were able to return home to see husband, children and other family members? Imagine coming to a small rural town, not having a Black community to socialize with, to turn to in times of need, to commiserate with, to worship with.

In 1900 the Carroll household consisted of businessman Edward H. Carroll, his wife Susie, a music teacher, their nineteen-year-old son Edward Lee, his wife Edith and Mary Corbett. Corbett was thirty-four and was hired prior t0 1900 to take care of the household when Edward was a child.

By 1910 Edward Lee, known as Lee, to differentiate himself from his father, had joined the family business. Edith had given birth two years earlier to a son, Edward H., and Mary Foy had joined the household as domestic servant. Mary Corbett was living with and working for a family in Hopkinton, NH.

Tragedy would strike the Carroll family in the next decade. Edward, the father died of heart disease in 1917. His son Lee died during the flu epidemic in January 1919. In 1920 the census shows that Susie and Edith were managing the household with the help of domestic servant Mary Howard and trying to keep their husbands’ businesses operating. Young Edward and James were 12 and 6 years old. Mary Howard age 38 had her hands full.

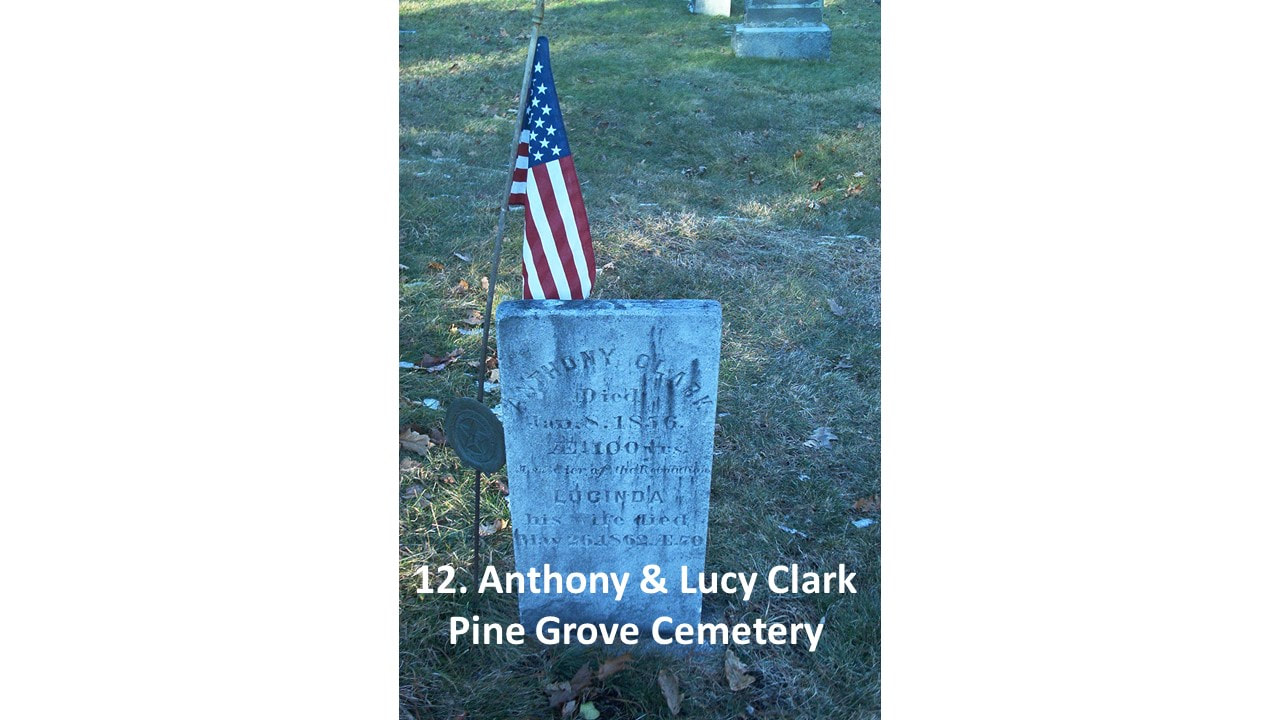

Pine Grove Cemetery – Anthony & Lucy Clark

Anthony Clark may have been small of stature (5’3”) but he loomed large in the surrounding community with his ability to play fiddle and call a dance at any opportunity. In fact, he was described as a “dance master.” Clark operated weekly dancing classes at various halls and inns in western Merrimack County. Theresa Harvey wrote about her memories of him performing during a muster held at her Uncle Jonathan’s homestead (Musterfield Farm in Sutton) around 1823:

After inspection the men were dismissed for dinner… Meantime, at the house, another kind of evolutions [i.e., military maneuvers] had been going on, Tony Clark with his fiddle acting as inspector-general. As soon as possible after the dinner tables were cleared away the hall was made ready for the dancers...Anthony Clark, the fiddler and dancing master, probably did more toward instructing the young people in the arts and graces of politeness and good manners than any other man of his day and generation.

Clark was nineteen when he enlisted for service for one month in October 1799 from Dracut, Massachusetts. He re-enlisted with Lt. Col. John Brook’s Seventh Massachusetts Regiment, which was stationed near West Point, New York. Clark was listed on the muster rolls at Camp Peekskill and York Huts and was “on command at the lines,” meaning he was engaged in active duty during his time of service. He received his final discharge on November 15, 1783, when his regiment disbanded. It is not certain if he returned to Dracut upon completion of his service, but according to pension records his military papers were destroyed in a house fire in Dunbarton, New Hampshire sometime in the 1790s. Clark wasn’t listed on the 1790 Dunbarton census but may have been living with either the Moors, Porters, or Pages as these families were also headed by black veterans of the American Revolution.

By 1795, Clark was paying a poll tax in Sutton, New Hampshire and by 1810 he had moved to the neighboring town of Warner. On January 12, 1804, Clark married Lucinda (Lucy) Moor of Canterbury, New Hampshire. Congregational minister Rev. William Kelly conducted the ceremony in Warner. None of the Clark’s ten children appear in the vital records of either Sutton or Warner, although they were listed in Anthony’s Revolutionary War pension application and in the census. Vital statistics of black families commonly went unrecorded. They were living on the land of Leonard Harriman’s on the road to East Sutton. Clark was able to supplement his earnings as a tenement farmer and cordwainer and by playing in local taverns and at muster events.

Clark died January 8, 1856, at the recorded age of one hundred. A military service was held in his honor, and he was buried in the Pine Grove Cemetery. Lucy, his wife, was buried by his side after her death on May 26, 1862. The Clarks are the only black family with a headstone marking their burial place in Warner. Several of the Clark children remained in the area after reaching adulthood. The sons worked as laborers, farmers, and mill hands. The Clark daughters married men who worked as musician, basket maker, and laborer. None of his children were known to have taken up their father’s profession of fiddling and calling dances.

Anthony Clark may have been small of stature (5’3”) but he loomed large in the surrounding community with his ability to play fiddle and call a dance at any opportunity. In fact, he was described as a “dance master.” Clark operated weekly dancing classes at various halls and inns in western Merrimack County. Theresa Harvey wrote about her memories of him performing during a muster held at her Uncle Jonathan’s homestead (Musterfield Farm in Sutton) around 1823:

After inspection the men were dismissed for dinner… Meantime, at the house, another kind of evolutions [i.e., military maneuvers] had been going on, Tony Clark with his fiddle acting as inspector-general. As soon as possible after the dinner tables were cleared away the hall was made ready for the dancers...Anthony Clark, the fiddler and dancing master, probably did more toward instructing the young people in the arts and graces of politeness and good manners than any other man of his day and generation.

Clark was nineteen when he enlisted for service for one month in October 1799 from Dracut, Massachusetts. He re-enlisted with Lt. Col. John Brook’s Seventh Massachusetts Regiment, which was stationed near West Point, New York. Clark was listed on the muster rolls at Camp Peekskill and York Huts and was “on command at the lines,” meaning he was engaged in active duty during his time of service. He received his final discharge on November 15, 1783, when his regiment disbanded. It is not certain if he returned to Dracut upon completion of his service, but according to pension records his military papers were destroyed in a house fire in Dunbarton, New Hampshire sometime in the 1790s. Clark wasn’t listed on the 1790 Dunbarton census but may have been living with either the Moors, Porters, or Pages as these families were also headed by black veterans of the American Revolution.

By 1795, Clark was paying a poll tax in Sutton, New Hampshire and by 1810 he had moved to the neighboring town of Warner. On January 12, 1804, Clark married Lucinda (Lucy) Moor of Canterbury, New Hampshire. Congregational minister Rev. William Kelly conducted the ceremony in Warner. None of the Clark’s ten children appear in the vital records of either Sutton or Warner, although they were listed in Anthony’s Revolutionary War pension application and in the census. Vital statistics of black families commonly went unrecorded. They were living on the land of Leonard Harriman’s on the road to East Sutton. Clark was able to supplement his earnings as a tenement farmer and cordwainer and by playing in local taverns and at muster events.

Clark died January 8, 1856, at the recorded age of one hundred. A military service was held in his honor, and he was buried in the Pine Grove Cemetery. Lucy, his wife, was buried by his side after her death on May 26, 1862. The Clarks are the only black family with a headstone marking their burial place in Warner. Several of the Clark children remained in the area after reaching adulthood. The sons worked as laborers, farmers, and mill hands. The Clark daughters married men who worked as musician, basket maker, and laborer. None of his children were known to have taken up their father’s profession of fiddling and calling dances.

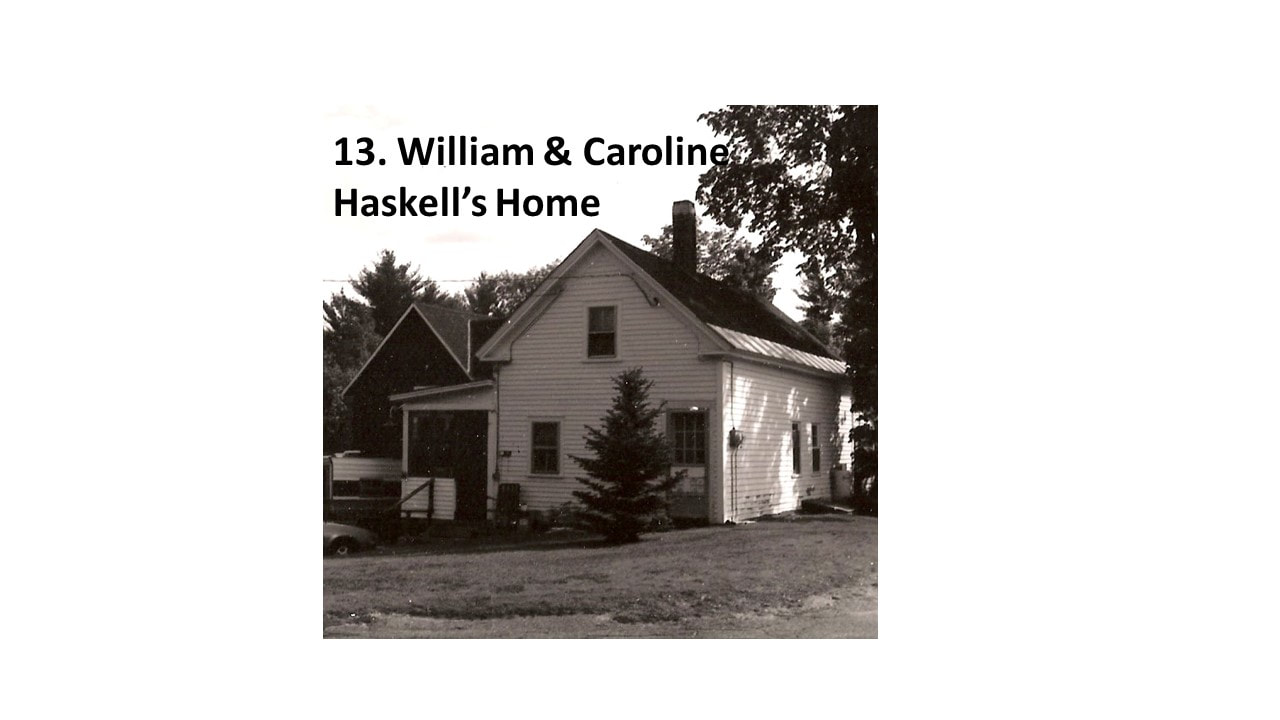

William Haskell House - 65 West Main St

William Haskell, a Black business man, was born to John and Lovee Haskell around 1819 in Warner, N.H. The Haskell family lived on Couchtown road and John probably labored on local farms or seasonally as a mill hand. William married Caroline Clark, daughter of Anthony and Lucy Clark of Warner. Their son James attended village schools in Warner until twenty years of age. An 1854 deed and promissory note for three-quarters of an acre purchased from Leonard and Sophronia Eaton described William as a basket maker. It is not certain how William learned the basket trade.

William and Caroline purchased land and buildings on Main Street from Harrison Robertson in 1860. They would mortgage this property off and on from the Robertson family for the next thirty years. It was highly unusual for Black residents to be able to own land in the center of town.

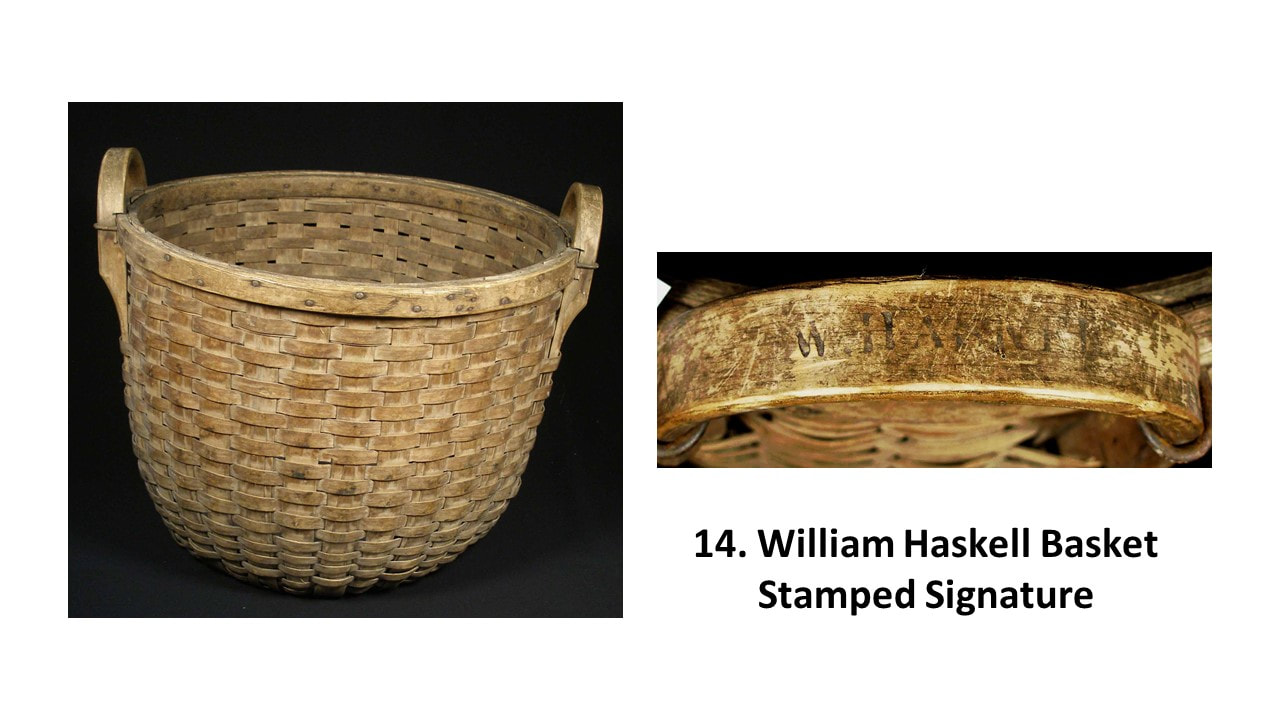

Caroline died in 1874 at the age of forty-seven. Seven months later William married widow Samantha Clark in Fisherville, NH. In 1879, William and Samantha sold their property to John Robertson for $750 and then rented from Robertson. The home and shop had the advantage of being on the road to the grounds of the Warner-Kearsarge Agricultural Fair Association which was a perfect location for Haskell to sell his sturdy baskets. Nineteenth-century business directories list Haskell’s basket-making business between 1885 and 1895. As early as 1881, however, his baskets were described in the newspaper as being as good as could be found in the market. He did the work by hand and in eight months produced four-hundred-bushel baskets. A signed Haskell bushel basket of brown ash was donated to the Warner Historical by Nancy Sibley Wilkins.

Samantha died in 1893. Three years later William died from a heart attack at the age of 77. The newspaper indicated he was buried in Warner but the identity of the cemetery for the burial of his family has not been determined. It may have been Coal Hearth Cemetery on Pumpkin Hill Road.

William Haskell, a Black business man, was born to John and Lovee Haskell around 1819 in Warner, N.H. The Haskell family lived on Couchtown road and John probably labored on local farms or seasonally as a mill hand. William married Caroline Clark, daughter of Anthony and Lucy Clark of Warner. Their son James attended village schools in Warner until twenty years of age. An 1854 deed and promissory note for three-quarters of an acre purchased from Leonard and Sophronia Eaton described William as a basket maker. It is not certain how William learned the basket trade.

William and Caroline purchased land and buildings on Main Street from Harrison Robertson in 1860. They would mortgage this property off and on from the Robertson family for the next thirty years. It was highly unusual for Black residents to be able to own land in the center of town.

Caroline died in 1874 at the age of forty-seven. Seven months later William married widow Samantha Clark in Fisherville, NH. In 1879, William and Samantha sold their property to John Robertson for $750 and then rented from Robertson. The home and shop had the advantage of being on the road to the grounds of the Warner-Kearsarge Agricultural Fair Association which was a perfect location for Haskell to sell his sturdy baskets. Nineteenth-century business directories list Haskell’s basket-making business between 1885 and 1895. As early as 1881, however, his baskets were described in the newspaper as being as good as could be found in the market. He did the work by hand and in eight months produced four-hundred-bushel baskets. A signed Haskell bushel basket of brown ash was donated to the Warner Historical by Nancy Sibley Wilkins.

Samantha died in 1893. Three years later William died from a heart attack at the age of 77. The newspaper indicated he was buried in Warner but the identity of the cemetery for the burial of his family has not been determined. It may have been Coal Hearth Cemetery on Pumpkin Hill Road.